TheUrbanist.org, Conor Bronsdon (Guest Contributor)

We know two things are true: we need more housing—1.8 million more people are expected to move to the Puget Sound region before 2050—and our region is falling behind our climate goals, as evidenced by the fires raging across the West Coast and the smoke choking off our ability to breath.

Yet people are still moving here in droves, and why wouldn’t they? Washington State is beautiful, offers economic juggernauts in the form of companies such as Amazon and Microsoft, a continually growing tech community that is powering the innovations that will shape our future. Plus, with a temperate climate, we are likely to be able to ideal with the effects of climate change for longer than many other regions.

With potentially millions more people on their way over the next 30 years, we need to build more housing–and if we’re going to meet our climate goals, we need to do so sustainably. Otherwise, we risk merely exacerbating our climate problems–concrete and steel production account for 14% of global emissions to date, and buildings in the US account for about 40% of our total energy use. Mandating or heavily incentivizing more Passive House buildings in the Pacific Northwest might be the best way to do that, while also helping us to combat the air pollution risks posed by forest fires and other results of climate change.

What is Passive House?

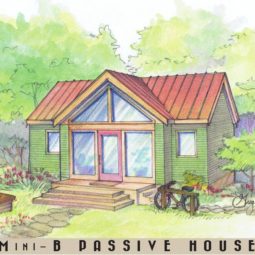

Passive House is an energy standard for high-performance buildings that provides 100% fresh filtered ventilation, uses very little energy–40-60% less energy than a normal building–and requires almost no energy for heating or cooling, significantly reducing the ecological footprint of new buildings.

The five building-science principles that passive buildings are designed with are:

- Continuous insulation throughout the building without any ‘thermal bridging’ (places where heat can escape through the insulation

- Airtight enclosure, preventing outside air from infiltrating and minimizing conditioned air loss

- Balanced heat- and moisture-recovery ventilation that provides 100% fresh, filtered air–something that is critical to address as air pollution rises and the risk of wildfires increases due to climate change

- High-performance windows and doors (triple-paned windows for our region’s climate) with correct solar orientation and shading–they should exploit the sun’s energy for heating purposes and minimize overheating during hot times

- Minimal space conditioning system (e.g., the systems responsible for heating or cooling, or otherwise affecting the spaces in a building), enabled by smart design – this ensures that future work will require smaller and even more efficient systems

When used together, these design principles result in buildings that are super energy efficient and tightly designed with no excess air or heat escaping. The heat gain from people within the building as well as the electronic appliances – even that of televisions and other low heat appliances–is accounted for and used to heat the space and keep it at a proper level. In conjunction with triple-pane windows, you get buildings that remain at comfortable temperatures year-round with little need for energy intensive heating or cooling. Another favorite feature of passive designed buildings for many tenants is the lack of external noise: the tight design of the buildings makes it so that the sounds of a city, whether sirens, roadways, or anything else are minimized. Add this to extremely low energy bills, and these buildings are a great place to live.

All in all, Passive House buildings provide both security against the impacts of climate change (healthy air, reduced emissions and helping regulate the temperature in case of spikes), as well as a solution to limit the carbon emissions that are driving climate change.

What’s stopping more Passive House?

If you’re reading this, I’m sure you’re thinking; this sounds great! Why aren’t we seeing more of these buildings? Sadly, we’ve yet to incentivize Passive House design. Instead, Passive House buildings–energy efficient and able to help us reach our region’s climate targets while also providing the housing we need–are often bogged down in a time-consuming and expensive design review process with a ton of subjectivity. Homeowners who want to block projects from happening because they “disrupt neighborhood character” can easily bog down projects, making them too expensive to proceed and ignoring the needs of the city and the plight of renters.

In addition, many of the pieces that Design Review tends to prioritize such as use of brick, modulation, and lots of windows, make buildings significantly less energy efficient. This makes it extremely hard to get Passive House projects through Design Review with City staff and design review board volunteers who are unfamiliar with Passive House permitting.

One example of the challenge of permitting and building Passive House projects is Sound West Group’s 66-unit apartment building proposed at 320 Queen Anne Ave N. Located in the heart of Lower Queen Anne, the building is scheduled to open in January. The project is a Passive House design and was 35% above the Priority Green requirement for Seattle’s permit process in a highly walkable and transit-accessible neighborhood, the kind of project that we need more of to meet our housing and climate goals. The goal of the Priority Green Expedited program is to shorten the time it takes to get a construction permit as long as the building meets strict green building rating standards.

How to incentivize Passive House design

We are in both a climate crisis and a housing crisis: we know we need to prioritize energy-efficient buildings while building a massive amount of housing in our region. One of the best ways to do this is to incentivize Passive House design in our region: we need to exempt Passive House projects from Design Review to achieve this.

Developers will take advantage of this significant incentive, encouraging energy-efficient buildings within our region. The Height in Vanouver, BC, is a Passive House certified apartment building. (Creative Commons photo by Lloyd Alter / Treehugger) “Removing design review would be a great incentive and allow us to build green projects faster and encouraging other developers who aren’t building Passive Houses too, they could save six months, eight months, and a bunch of unnecessary costs,” Ritchie said.

To further expedite needed green buildings, we can expand the Priority Green program. Currently, priority permitting applies only to the building permits and not the master use permitting, as in the case of the Queen Anne Ave project, which had their right of way permit delayed. For that project, Design Review started back in 2016, yet they’re not slated to open their “Priority Green” supported building until 2021. Cities should also consider permitting fast tracks and perhaps amending building codes as necessary to make it simpler for Passive House to meet code without exemptions–we need buildings with fully filtered air and incredibly low energy usage.

To really go all in, we can also look at low-interest loan programs or density bonuses for Passive House projects. Seattle and other municipalities can encourage this whole process by using their authority under local Green New Deal legislation to invest in training to expand our regional capacity for these buildings, as suggested by local Passive House architect Andrew Grant Houston. This also fixes the problem of understanding Passive House; one of the challenges with Design Review is that community members may not be aware or trained on Passive House design, adding to the time it languishes in Design Review. City staff, already familiar with design processes, can be more easily trained up on Passive House specific standards. Sound West’s Weber echoed this. “[The Queen Anne Avenue project] went through four rounds of building comments and I think part of the reason is that the city isn’t aware enough of Passive House projects,” Weber said. “We need to do education.”

The moment we are in is too great for us to allow red-tape filled processes to bog us down, these buildings will still have to meet zoning and permitting standards, but by exempting Passive House buildings from Design Review, we can ensure these projects become the standard for the region and that our new housing is built with energy-efficient design. With a rising need for housing and more energy-efficient buildings, we cannot afford to wait.

We hope you loved this article. If so, please consider subscribing or donating. The Urbanist is a non-profit that depends on donations from readers like you.

« Previous Story Next Story: SOLIS named project of the week